Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

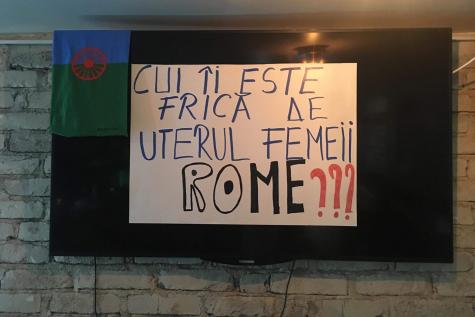

Romania

Roma Women in Romania Face Old and New Threats to Abortion Care Access

Roma women and girls face multiple barriers to abortion care in Romania. Far more needs to be done to protect their rights, says Roxana-Magdalena Oprea of E-Romnja.

Most Popular This Week

Romania

Roma Women in Romania Face Old and New Threats to Abortion Care Access

For Roma women and girls in Romania, the struggle to access abortion care brings them into contact with horrific levels of racism and discrimination, hardw

Croatia: Obstacles to abortion care make access virtually non-existent

Hitting the road in the desperate search for abortion care

Romania

High costs and broken health system freeze many out of abortion care in Romania

On paper, abortion care is legal up to 14 weeks in Romania – though only free in emergencies – and should be provided by all hospitals with obstetrics and gynaecology departments.

Germany

Germany's archaic abortion law creates huge burden for people needing care

For a country long reputed to have one of the more progressive healthcare systems in Europe, Germany’s law on abortion – a health issue affecting millions of people – remains firm

Sexuality education keeps young people safe from harm

Comprehensive sexuality and relationship education is a vital prevention tool in the fight

Belgium’s consent law is clear: Absence of no doesn’t mean yes

‘Rape isn’t always something that happens when you are dragged into an alleyway’, says Heleen Heysse, Policy Officer at

Legislating the path to consent: Spain's Yes Means Yes law

‘Everyone has the right to live without violence. You can have sex without love, but always with care’.

Anything less than yes is rape: the campaign for a consent-based rape law in Sweden

The absence of a ‘no’ is not an implicit yes. This is the overarching principle of a long-fought Swedish ‘consent law’ aimed at disman

Filter our stories by:

- Albanian Center for Population and Development

- Associação Para o Planeamento da Família

- Bulgarian Family Planning and Sexual Health Association

- (-) Health Education and Research Association (HERA) - North Macedonia

- Institute for Population and Development

- Mouvement Français pour le Planning Familial

- Polish Women's Strike

- Pro Familia - Germany

- SECS – Contraception and Sexual Education Society, Romania

- Serbian Association for Sexual and Reproductive Rights

| 15 October 2022

"COVID measures curtailed the freedom of movement of people who needed sexual and reproductive healthcare the most."

We spoke to young people from the Western Balkans about how their access to sexual and reproductive health and rights was affected by the COVID pandemic, and asked them about their vision for re-designing a more youth-friendly future in which young people can flourish. Yellow is a 22-year-old student from Skopje, North Macedonia. Yellow, describe your experience of access to SRHR* education, information and care before and during COVID. During the beginning of the pandemic, my access (as a student) to health services was limited due to bureaucratic obstacles to enjoying the right to free health care. Sexual and reproductive health, as well as non-COVID services, were deprioritized, hence access to them was difficult. Since COVID, things are slowly starting to return to normal, but due to the global economic situation, some of the services offered by the NGO sector are being cut and we are working strictly with certain groups of individuals who are being targeted at the moment. I have witnessed young people being turned away from accessing SRHR-related services because they do not belong to a certain group. Did anything change for the better for you during the pandemic in terms of access to SRHR? Has this continued since COVID is no longer an urgent crisis? What has improved is access to SHRH education, due to the expansion of availability with new digital tools. But many of these alternatives, which were of great importance in the time of COVID, have been cut off by the easing of restrictions. What was the biggest obstacle to your SRHR during the pandemic? How could decision-makers/medical professionals have removed this obstacle? The main obstacle during the pandemic was the complete deprioritization of all health care at the expense of COVID. Due to the novelty of dealing with a pandemic, the government and institutions had difficulties in managing things. Additionally, I believe that gender blindness in making these decisions was shown by curtailing the freedom and movement of people who were most in need of SRH services. This could have been prevented by including the perspective of different marginalised groups in the creation of recommendations and protocols to deal with the pandemic. What lessons do you think governments and professionals working with young people should learn from the COVID experience about how to look after young people’s health and well-being in a crisis? I don't think any new lessons were learned, unfortunately. I hope that the experience of this pandemic will help in creating programs and protocols that will prevent similar situations like this. In a number of states, states of emergency have been misused to push political agendas. Additionally young people were again placed at the bottom of the list for maintaining their well-being, reinforcing the stereotype that health care should not be a priority for young people because of their 'youth/age'. What is your number 1 recommendation on what is needed to make services more youth-friendly? What difference would this make in the life of a young person like you or your friends? Very easy: ask and listen to young people. High quality, youth-friendly services should be available and accessible to young people in appropriate locations. Employees need to be motivated and ready to adapt to work with young people. Perhaps an additional piece of advice would be to invest in young people who can be professionally involved in these institutions. * SRHR = sexual and reproductive health and rights Interview conducted by Anamarija Danevska, a member of the regional youth group of the IPPF EN project Youth Voices, Youth Choices, funded by MSD for Mothers

| 25 October 2022

"COVID measures curtailed the freedom of movement of people who needed sexual and reproductive healthcare the most."

We spoke to young people from the Western Balkans about how their access to sexual and reproductive health and rights was affected by the COVID pandemic, and asked them about their vision for re-designing a more youth-friendly future in which young people can flourish. Yellow is a 22-year-old student from Skopje, North Macedonia. Yellow, describe your experience of access to SRHR* education, information and care before and during COVID. During the beginning of the pandemic, my access (as a student) to health services was limited due to bureaucratic obstacles to enjoying the right to free health care. Sexual and reproductive health, as well as non-COVID services, were deprioritized, hence access to them was difficult. Since COVID, things are slowly starting to return to normal, but due to the global economic situation, some of the services offered by the NGO sector are being cut and we are working strictly with certain groups of individuals who are being targeted at the moment. I have witnessed young people being turned away from accessing SRHR-related services because they do not belong to a certain group. Did anything change for the better for you during the pandemic in terms of access to SRHR? Has this continued since COVID is no longer an urgent crisis? What has improved is access to SHRH education, due to the expansion of availability with new digital tools. But many of these alternatives, which were of great importance in the time of COVID, have been cut off by the easing of restrictions. What was the biggest obstacle to your SRHR during the pandemic? How could decision-makers/medical professionals have removed this obstacle? The main obstacle during the pandemic was the complete deprioritization of all health care at the expense of COVID. Due to the novelty of dealing with a pandemic, the government and institutions had difficulties in managing things. Additionally, I believe that gender blindness in making these decisions was shown by curtailing the freedom and movement of people who were most in need of SRH services. This could have been prevented by including the perspective of different marginalised groups in the creation of recommendations and protocols to deal with the pandemic. What lessons do you think governments and professionals working with young people should learn from the COVID experience about how to look after young people’s health and well-being in a crisis? I don't think any new lessons were learned, unfortunately. I hope that the experience of this pandemic will help in creating programs and protocols that will prevent similar situations like this. In a number of states, states of emergency have been misused to push political agendas. Additionally young people were again placed at the bottom of the list for maintaining their well-being, reinforcing the stereotype that health care should not be a priority for young people because of their 'youth/age'. What is your number 1 recommendation on what is needed to make services more youth-friendly? What difference would this make in the life of a young person like you or your friends? Very easy: ask and listen to young people. High quality, youth-friendly services should be available and accessible to young people in appropriate locations. Employees need to be motivated and ready to adapt to work with young people. Perhaps an additional piece of advice would be to invest in young people who can be professionally involved in these institutions. * SRHR = sexual and reproductive health and rights Interview conducted by Anamarija Danevska, a member of the regional youth group of the IPPF EN project Youth Voices, Youth Choices, funded by MSD for Mothers

| 07 December 2016

Sexual health empowerment for young people with disabilities

In Macedonia, HERA's special educator, Zaklina Stepanoska, recalls the reactions of parents when she explained the programme. They were running an inititiave for young people with disabilities to learn about their sexual health. “There were parents who cried when I told them about this,” she says. “I asked them why and they told me it was because they had thought their children, who were in their mid 20s, would never fall in love or have girlfriends. It touched them very much and surprised them that somebody had thought about their children receiving this education and maybe having a relationship.” The programme has already been useful in changing behaviour in the centre. “In the spring and summer, when we're outside in the garden a lot, the girls will go crazy when some guy walks past, because they like boys,” Zaklina explains. “They will shout and talk to them even though they don't know them. So we make them understand that they can say 'hi' to people they already know, but not strangers, unless we allow them to. “We also had a big problem with boys masturbating. Since the sessions on public and private space we don't have this problem any more. When a staff member sees that someone is going to start doing it, they ask them to go to the toilet, or they take them to a private space. They don't say 'stop', because if they're stopped they can become aggressive. Back then they didn't know how to deal with this. Now they tell them it's not suitable to do in public. And the boys hardly ever try to do it any more. “We had a problem, too, with girls not knowing how to put sanitary towels in. Their parents would put a towel in at home and the girl would forget about it. Now they bring towels themselves and they know how to change them. “The young people are very interested in the programme. It's something new. They're very interested in the fact that can become independent outside the centre, that they can go out alone, that they can be with someone, with a boyfriend or girlfriend, and that they are allowed to do that. Because their parents usually scorn them when they started talking about these things. “There are changes in the way they behave. They don't talk to strangers any more. They know the appropriate words for parts of the body, and they're not embarrassed to say them out loud any more. In the beginning when we had individual sessions the girls would start crying and saying 'this is shameful'. They would not even utter the words. Now they're free to talk about it. They have become closer to us. They would come to us and say if they have a crush on somebody. They laugh about it, they tease each other. They're much more relaxed than they used to be. “There are two users here who act as boyfriend and girlfriend in the centre. They live far apart but here they watch films together, they dance, they kiss. They can't be separated! It's a positive thing; they are happier.”

| 09 May 2025

Sexual health empowerment for young people with disabilities

In Macedonia, HERA's special educator, Zaklina Stepanoska, recalls the reactions of parents when she explained the programme. They were running an inititiave for young people with disabilities to learn about their sexual health. “There were parents who cried when I told them about this,” she says. “I asked them why and they told me it was because they had thought their children, who were in their mid 20s, would never fall in love or have girlfriends. It touched them very much and surprised them that somebody had thought about their children receiving this education and maybe having a relationship.” The programme has already been useful in changing behaviour in the centre. “In the spring and summer, when we're outside in the garden a lot, the girls will go crazy when some guy walks past, because they like boys,” Zaklina explains. “They will shout and talk to them even though they don't know them. So we make them understand that they can say 'hi' to people they already know, but not strangers, unless we allow them to. “We also had a big problem with boys masturbating. Since the sessions on public and private space we don't have this problem any more. When a staff member sees that someone is going to start doing it, they ask them to go to the toilet, or they take them to a private space. They don't say 'stop', because if they're stopped they can become aggressive. Back then they didn't know how to deal with this. Now they tell them it's not suitable to do in public. And the boys hardly ever try to do it any more. “We had a problem, too, with girls not knowing how to put sanitary towels in. Their parents would put a towel in at home and the girl would forget about it. Now they bring towels themselves and they know how to change them. “The young people are very interested in the programme. It's something new. They're very interested in the fact that can become independent outside the centre, that they can go out alone, that they can be with someone, with a boyfriend or girlfriend, and that they are allowed to do that. Because their parents usually scorn them when they started talking about these things. “There are changes in the way they behave. They don't talk to strangers any more. They know the appropriate words for parts of the body, and they're not embarrassed to say them out loud any more. In the beginning when we had individual sessions the girls would start crying and saying 'this is shameful'. They would not even utter the words. Now they're free to talk about it. They have become closer to us. They would come to us and say if they have a crush on somebody. They laugh about it, they tease each other. They're much more relaxed than they used to be. “There are two users here who act as boyfriend and girlfriend in the centre. They live far apart but here they watch films together, they dance, they kiss. They can't be separated! It's a positive thing; they are happier.”

| 15 October 2022

"COVID measures curtailed the freedom of movement of people who needed sexual and reproductive healthcare the most."

We spoke to young people from the Western Balkans about how their access to sexual and reproductive health and rights was affected by the COVID pandemic, and asked them about their vision for re-designing a more youth-friendly future in which young people can flourish. Yellow is a 22-year-old student from Skopje, North Macedonia. Yellow, describe your experience of access to SRHR* education, information and care before and during COVID. During the beginning of the pandemic, my access (as a student) to health services was limited due to bureaucratic obstacles to enjoying the right to free health care. Sexual and reproductive health, as well as non-COVID services, were deprioritized, hence access to them was difficult. Since COVID, things are slowly starting to return to normal, but due to the global economic situation, some of the services offered by the NGO sector are being cut and we are working strictly with certain groups of individuals who are being targeted at the moment. I have witnessed young people being turned away from accessing SRHR-related services because they do not belong to a certain group. Did anything change for the better for you during the pandemic in terms of access to SRHR? Has this continued since COVID is no longer an urgent crisis? What has improved is access to SHRH education, due to the expansion of availability with new digital tools. But many of these alternatives, which were of great importance in the time of COVID, have been cut off by the easing of restrictions. What was the biggest obstacle to your SRHR during the pandemic? How could decision-makers/medical professionals have removed this obstacle? The main obstacle during the pandemic was the complete deprioritization of all health care at the expense of COVID. Due to the novelty of dealing with a pandemic, the government and institutions had difficulties in managing things. Additionally, I believe that gender blindness in making these decisions was shown by curtailing the freedom and movement of people who were most in need of SRH services. This could have been prevented by including the perspective of different marginalised groups in the creation of recommendations and protocols to deal with the pandemic. What lessons do you think governments and professionals working with young people should learn from the COVID experience about how to look after young people’s health and well-being in a crisis? I don't think any new lessons were learned, unfortunately. I hope that the experience of this pandemic will help in creating programs and protocols that will prevent similar situations like this. In a number of states, states of emergency have been misused to push political agendas. Additionally young people were again placed at the bottom of the list for maintaining their well-being, reinforcing the stereotype that health care should not be a priority for young people because of their 'youth/age'. What is your number 1 recommendation on what is needed to make services more youth-friendly? What difference would this make in the life of a young person like you or your friends? Very easy: ask and listen to young people. High quality, youth-friendly services should be available and accessible to young people in appropriate locations. Employees need to be motivated and ready to adapt to work with young people. Perhaps an additional piece of advice would be to invest in young people who can be professionally involved in these institutions. * SRHR = sexual and reproductive health and rights Interview conducted by Anamarija Danevska, a member of the regional youth group of the IPPF EN project Youth Voices, Youth Choices, funded by MSD for Mothers

| 25 October 2022

"COVID measures curtailed the freedom of movement of people who needed sexual and reproductive healthcare the most."

We spoke to young people from the Western Balkans about how their access to sexual and reproductive health and rights was affected by the COVID pandemic, and asked them about their vision for re-designing a more youth-friendly future in which young people can flourish. Yellow is a 22-year-old student from Skopje, North Macedonia. Yellow, describe your experience of access to SRHR* education, information and care before and during COVID. During the beginning of the pandemic, my access (as a student) to health services was limited due to bureaucratic obstacles to enjoying the right to free health care. Sexual and reproductive health, as well as non-COVID services, were deprioritized, hence access to them was difficult. Since COVID, things are slowly starting to return to normal, but due to the global economic situation, some of the services offered by the NGO sector are being cut and we are working strictly with certain groups of individuals who are being targeted at the moment. I have witnessed young people being turned away from accessing SRHR-related services because they do not belong to a certain group. Did anything change for the better for you during the pandemic in terms of access to SRHR? Has this continued since COVID is no longer an urgent crisis? What has improved is access to SHRH education, due to the expansion of availability with new digital tools. But many of these alternatives, which were of great importance in the time of COVID, have been cut off by the easing of restrictions. What was the biggest obstacle to your SRHR during the pandemic? How could decision-makers/medical professionals have removed this obstacle? The main obstacle during the pandemic was the complete deprioritization of all health care at the expense of COVID. Due to the novelty of dealing with a pandemic, the government and institutions had difficulties in managing things. Additionally, I believe that gender blindness in making these decisions was shown by curtailing the freedom and movement of people who were most in need of SRH services. This could have been prevented by including the perspective of different marginalised groups in the creation of recommendations and protocols to deal with the pandemic. What lessons do you think governments and professionals working with young people should learn from the COVID experience about how to look after young people’s health and well-being in a crisis? I don't think any new lessons were learned, unfortunately. I hope that the experience of this pandemic will help in creating programs and protocols that will prevent similar situations like this. In a number of states, states of emergency have been misused to push political agendas. Additionally young people were again placed at the bottom of the list for maintaining their well-being, reinforcing the stereotype that health care should not be a priority for young people because of their 'youth/age'. What is your number 1 recommendation on what is needed to make services more youth-friendly? What difference would this make in the life of a young person like you or your friends? Very easy: ask and listen to young people. High quality, youth-friendly services should be available and accessible to young people in appropriate locations. Employees need to be motivated and ready to adapt to work with young people. Perhaps an additional piece of advice would be to invest in young people who can be professionally involved in these institutions. * SRHR = sexual and reproductive health and rights Interview conducted by Anamarija Danevska, a member of the regional youth group of the IPPF EN project Youth Voices, Youth Choices, funded by MSD for Mothers

| 07 December 2016

Sexual health empowerment for young people with disabilities

In Macedonia, HERA's special educator, Zaklina Stepanoska, recalls the reactions of parents when she explained the programme. They were running an inititiave for young people with disabilities to learn about their sexual health. “There were parents who cried when I told them about this,” she says. “I asked them why and they told me it was because they had thought their children, who were in their mid 20s, would never fall in love or have girlfriends. It touched them very much and surprised them that somebody had thought about their children receiving this education and maybe having a relationship.” The programme has already been useful in changing behaviour in the centre. “In the spring and summer, when we're outside in the garden a lot, the girls will go crazy when some guy walks past, because they like boys,” Zaklina explains. “They will shout and talk to them even though they don't know them. So we make them understand that they can say 'hi' to people they already know, but not strangers, unless we allow them to. “We also had a big problem with boys masturbating. Since the sessions on public and private space we don't have this problem any more. When a staff member sees that someone is going to start doing it, they ask them to go to the toilet, or they take them to a private space. They don't say 'stop', because if they're stopped they can become aggressive. Back then they didn't know how to deal with this. Now they tell them it's not suitable to do in public. And the boys hardly ever try to do it any more. “We had a problem, too, with girls not knowing how to put sanitary towels in. Their parents would put a towel in at home and the girl would forget about it. Now they bring towels themselves and they know how to change them. “The young people are very interested in the programme. It's something new. They're very interested in the fact that can become independent outside the centre, that they can go out alone, that they can be with someone, with a boyfriend or girlfriend, and that they are allowed to do that. Because their parents usually scorn them when they started talking about these things. “There are changes in the way they behave. They don't talk to strangers any more. They know the appropriate words for parts of the body, and they're not embarrassed to say them out loud any more. In the beginning when we had individual sessions the girls would start crying and saying 'this is shameful'. They would not even utter the words. Now they're free to talk about it. They have become closer to us. They would come to us and say if they have a crush on somebody. They laugh about it, they tease each other. They're much more relaxed than they used to be. “There are two users here who act as boyfriend and girlfriend in the centre. They live far apart but here they watch films together, they dance, they kiss. They can't be separated! It's a positive thing; they are happier.”

| 09 May 2025

Sexual health empowerment for young people with disabilities

In Macedonia, HERA's special educator, Zaklina Stepanoska, recalls the reactions of parents when she explained the programme. They were running an inititiave for young people with disabilities to learn about their sexual health. “There were parents who cried when I told them about this,” she says. “I asked them why and they told me it was because they had thought their children, who were in their mid 20s, would never fall in love or have girlfriends. It touched them very much and surprised them that somebody had thought about their children receiving this education and maybe having a relationship.” The programme has already been useful in changing behaviour in the centre. “In the spring and summer, when we're outside in the garden a lot, the girls will go crazy when some guy walks past, because they like boys,” Zaklina explains. “They will shout and talk to them even though they don't know them. So we make them understand that they can say 'hi' to people they already know, but not strangers, unless we allow them to. “We also had a big problem with boys masturbating. Since the sessions on public and private space we don't have this problem any more. When a staff member sees that someone is going to start doing it, they ask them to go to the toilet, or they take them to a private space. They don't say 'stop', because if they're stopped they can become aggressive. Back then they didn't know how to deal with this. Now they tell them it's not suitable to do in public. And the boys hardly ever try to do it any more. “We had a problem, too, with girls not knowing how to put sanitary towels in. Their parents would put a towel in at home and the girl would forget about it. Now they bring towels themselves and they know how to change them. “The young people are very interested in the programme. It's something new. They're very interested in the fact that can become independent outside the centre, that they can go out alone, that they can be with someone, with a boyfriend or girlfriend, and that they are allowed to do that. Because their parents usually scorn them when they started talking about these things. “There are changes in the way they behave. They don't talk to strangers any more. They know the appropriate words for parts of the body, and they're not embarrassed to say them out loud any more. In the beginning when we had individual sessions the girls would start crying and saying 'this is shameful'. They would not even utter the words. Now they're free to talk about it. They have become closer to us. They would come to us and say if they have a crush on somebody. They laugh about it, they tease each other. They're much more relaxed than they used to be. “There are two users here who act as boyfriend and girlfriend in the centre. They live far apart but here they watch films together, they dance, they kiss. They can't be separated! It's a positive thing; they are happier.”